“Enclosure came and trampled on the grave, Of labours rights and left the poor a slave”

The story of how Epping Forest was saved is a complex campaign involving ancient laws and modern politicians, well-connected socialists, corporations, early conservationists and working-class activism.

Between 1760 and 1870, about 7 million acres (one sixth the area of England) was converted from shared common land to ‘profitable’ fenced off, private land. Enclosure was not a new problem, but the rate at which it advanced during this time forced many of the rural poor, who relied on common pastures for grazing animals and growing food, to flee to cities (particularly London) to find work, resulting in overcrowding and desperate living conditions as the demand for work outweighed need.

Enclosure didn’t just divide our land, it introduced a chasm in our social class system, and was an early glimpse of capitalism as we know it today.

Epping Forest & Enclosure

A new train line from London to Loughton was built during the mid-1800s, and later a line to Chingford, making it easy for Londoners to visit Epping Forest. Nicknamed the ‘cockney paradise’, there were donkey rides and retreats selling food and drink (Butler’s Retreat still exists as a cafe today). This in turn made owning land in the area more desirable.

By the early 1870s more than half of Epping Forest had been enclosed. It must have been a bitter irony for people who had been forced to move from countryside to city, only to have enclosure take away their respite from the dirty, crowded slums of the East End.

“... the grip of the land grabber is over us all; and commons and heaths of unmatched beauty and wildness have been enclosed for farmers or jerry-built upon by speculators in order to swell the illgotten revenues of some covetous aristocrat or greedy money-bag”

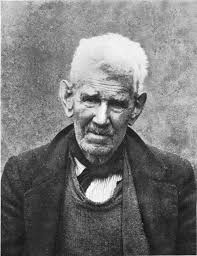

Thomas Willingale, a labourer from Loughton, played an important role in saving Epping Forest. It is his story – a wonderful collection of fact and folklore – that I want to focus on, not just because of my personal link to him (he is my 5 x Great Uncle) but because I was struck by the attitude to social class in the 1800s. Thomas is mocked in publications and media from the time; in some historical accounts his activism is totally erased, or he is referred to in passing, not by name but as a ‘common illiterate labourer’.

“These forests, so near the Metropolis are well known to be the nursery and resort of the most idle and profligate of men … those who object to the plans to enclose the Forest are seen as not only unpatriotic but to be condemning ‘the paupers’ offspring’ to a life of crime whereby they can only end on the gallows”

Epping Forest belonged to the Crown from the 12th century, and commoners were permitted to lop branches seven feet or more from the ground between 12 November and 23 April to use as firewood. This technique, called pollarding, leaves the lower branches for deer to feed on. Thomas believed that to retain this right lopping needed to start before midnight on the 11 November (St Martin’s Day), or else they would lose their ancient rights for ever. This was celebrated annually on Staples Hill, in Loughton with bonfires, torches and beer!

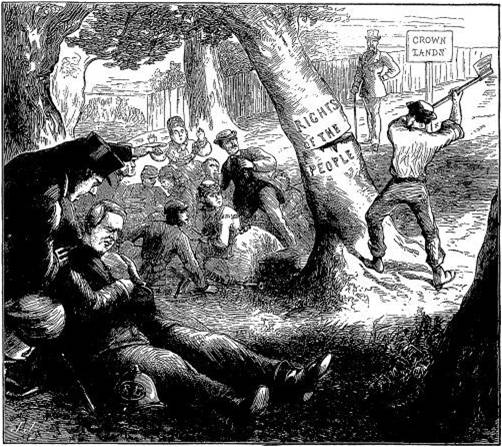

Staples Hill lopping celebrations, 11 November.

Reverend Maitland, Lord of the Manor in the Loughton area, had fenced off 1,316 acres of forest and had started construction of buildings and roads. For 16 years Thomas defied Maitland, ignored the fences and continued to lop the trees. Maitland tried all means to stop him; he offered large sums of money and issued a summons against Thomas to win possession of his cottage but ‘Old Tom’ stood his ground.

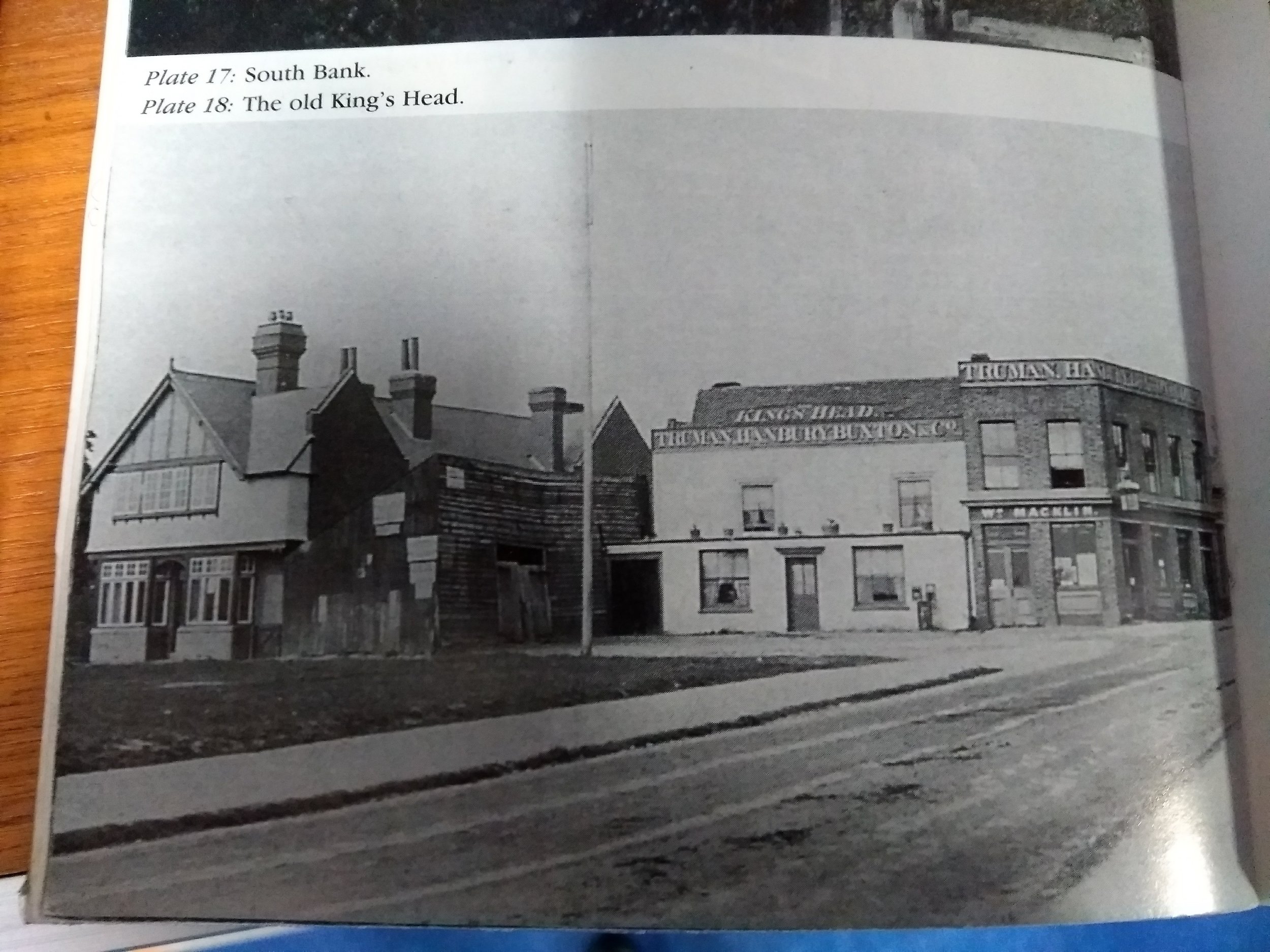

One of Maitland’s most devious plots was on 11 November 1859, when it is said he laid on food and beer for the local loppers at the King’s Head in Loughton. He had hoped to get them all drunk so that they forgot to go out before midnight to start lopping, thereby forfeiting their rights forever. Thomas wasn’t stupid, he enjoyed the refreshments and went out just before midnight, returning with the branch to present to Maitland at the pub.

Is this true? No one is really sure. I like to think it happened – it’s wonderfully evocative, and a perfect story to be made into a folk song. Watch this space! (Edit: ‘The Lopper and the Landgrabber’ on my Epping Forest themed album)

The conflict continued, and in 1866 Thomas’ son Samuel and his two cousins Alfred Willingale and William Higgins were in court for “injuring trees and stealing wood”. They were fined a small amount but refused to pay it and ended up in Ilford Jail to do seven days hard labour.

The enclosure movement was now a concern of the more affluent socialists of the time. The Commons Preservation Society was set up to protect public rights of way and common land and early members included Octavia Hill (who went on to found the National Trust), William Morris, Edward Buxton and Lord Elversley. They got wind of the Willingales’ story and felt it might help save Epping Forest. They gave Thomas £1000 to fight his case.

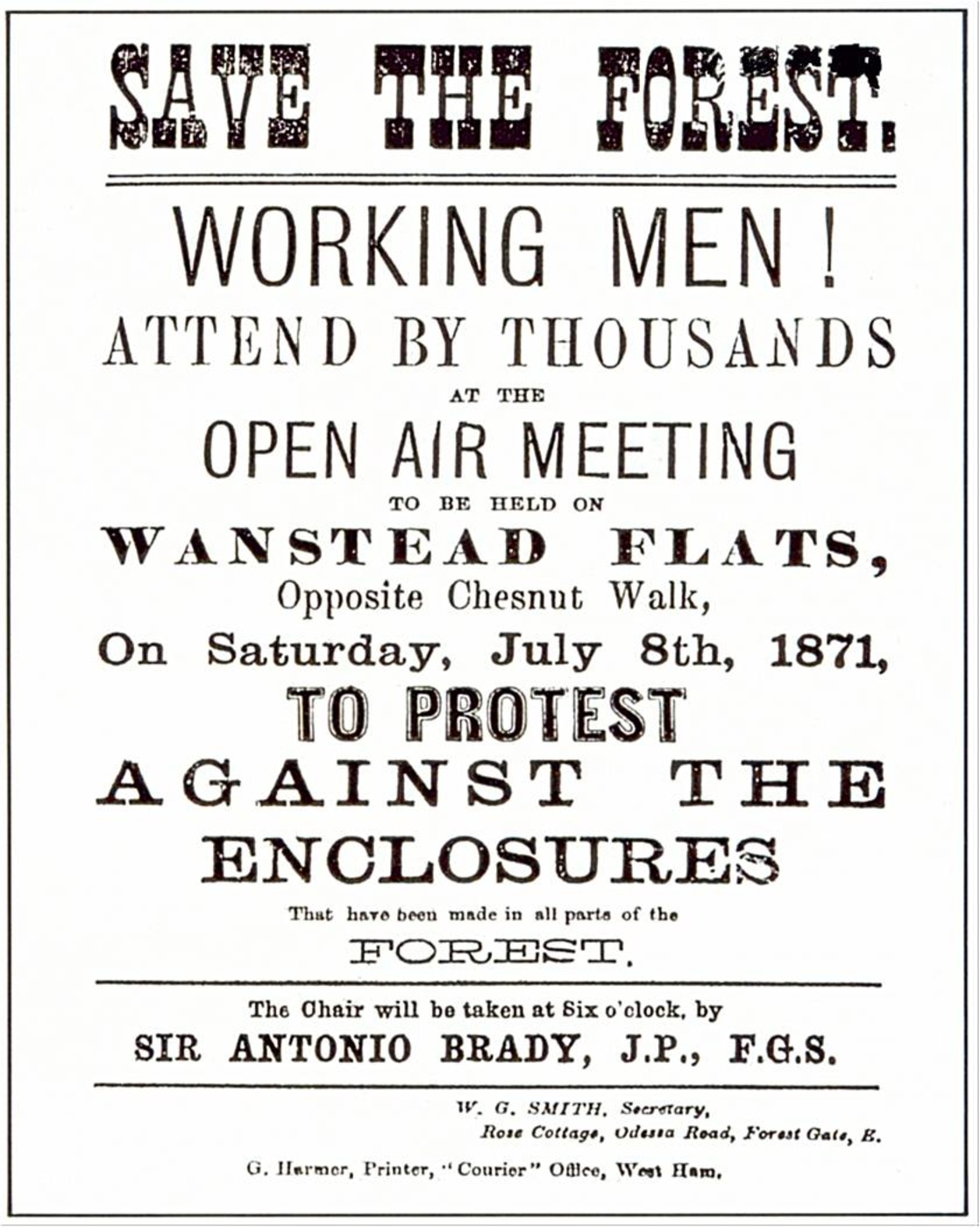

In July 1871 there was a mass demonstration on Wanstead Flats. This was a key moment and local campaigners rallied troops from the East End. The demonstrations were critical of the government and resulted in fences being torn down. It reached national news, and William Gladstone’s government, not keen on the bad press, rushed through the first of a series of acts prohibiting further enclosures while the case was investigated.

The Lords of the Manor wrongly assumed that when they bought the land from the Crown it eradicated any rights the commoners had. It wasn’t as clear cut as that, and a long and costly legal battle began. Thomas died in 1870 before the case was heard, but the process had stalled enclosure for four years, giving solicitors time to look into the history of the area and consult the Rolls of the Manor.

The City of London Corporation, which had recently bought land for a cemetery in Wanstead to which common rights were attached, stepped in to conclude the fight, and the Epping Forest Act was put in place in 1878. The forest is still managed by the City of London and protected in perpetuity for the recreation and enjoyment of visitors.

You’re no longer allowed to lop trees in Epping Forest, but grazing rights are still permitted. I remember a few occasions when I was a kid when cows went ‘off piste’ and walked down my street in Highams Park. A bizarre sight amongst the parked cars.

Epping Forest facts:

The Forest covers around 6000 acres – equivalent to over 3,300 football pitches

It has over one million trees, some of which are up to 1,000 years old – including 50,000 ancient pollards of Beech, Hornbeam and Oak.

It is thought that for every 100 trees lopped in the forest, 80 were by a Willingale.